Back Bedakol (Rangifer tarandus caribou) AVK گوزن جنگلی مهاجر Persian Metsäkaribu Finnish Caribou des bois French Erdei karibu Hungarian Skogskaribu NB Tuần lộc núi Vietnamese

| Boreal woodland caribou | |

|---|---|

| |

| Boreal woodland caribou in the southern Selkirk Mountains of Idaho in 2007 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Cervidae |

| Subfamily: | Capreolinae |

| Genus: | Rangifer |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | R. t. caribou

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Rangifer tarandus caribou (Gmelin, 1788)

| |

| |

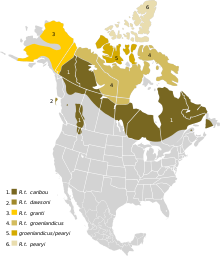

| Approximate range of boreal woodland caribou in 2003. Overlap with other subspecies of caribou is possible for contiguous range. 1. Rangifer tarandus caribou, which is subdivided into ecotypes: woodland (boreal), woodland (migratory) and woodland (mountain), 2. R. t. dawsoni (extinct 1908), 3. R. t. groenlandicus, 4. R. t. groenlandicus, 5. R. t. groenlandicus, 6. R. t. pearyi | |

The boreal woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou; but subject to a recent taxonomic revision. See Reindeer: Taxonomy), also known as Eastern woodland caribou, boreal forest caribou and forest-dwelling caribou, is a North American subspecies of reindeer (or caribou in North America) found primarily in Canada with small populations in the United States. Unlike the Porcupine caribou and barren-ground caribou, boreal woodland caribou are primarily (but not always) sedentary.[Notes 1][2][3][4][5]

The boreal woodland caribou is the third largest of the caribou ecotypes [6][7] after the Selkirk Mountains caribou and Osborn's caribou (see Reindeer: Taxonomy) and is darker[8] in color than the barren-ground caribou.[9] Valerius Geist, specialist on large North American mammals, described the "true" woodland caribou as "the uniformly dark, small-maned type with the frontally emphasized, flat-beamed antlers" which is "scattered thinly along the southern rim of North American caribou distribution". Geist asserted that "the true woodland caribou is very rare, in very great difficulties and requires the most urgent of attention", but suggests that this urgency is compromised by the inclusion of the Newfoundland caribou, the Labrador caribou, and Osborn's caribou in the Rangifer tarandus caribou subspecies. In Geist's opinion, the inclusion of these additional populations obscures the precarious position of the "true" woodland caribou.[8] A recent revision,[10] recognizing Labrador and Newfoundland caribou as distinct subspecies of woodland caribou, partially rectifies this problem.

They prefer lichen-rich, mature forests,[11] and mainly live in marshes, bogs, lakes and river regions.[12][13]

The historic range of the woodland caribou covered over half of present-day Canada,[4] stretching from Yukon to Newfoundland and Labrador. The national meta-population of this sedentary boreal ecotype spans the boreal forest from the Northwest Territories to Labrador (but not Newfoundland). Their former range stretched south into the contiguous United States. By 2019, the last individual in the Lower 48 (a female) was captured and taken to a rehab center in British Columbia, thus marking the extirpation of the caribou in the contiguous U.S.[14]

The boreal woodland caribou was designated as Threatened in 2002 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC).[15] Environment Canada reported in 2011 that there were approximately 34,000 boreal woodland caribou in 51 ranges remaining in Canada.(Environment Canada, 2011b).[16] In a joint report by the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) and the David Suzuki Foundation, on the status of boreal woodland caribou, it was claimed that "the biggest risk to caribou is industrial development, which fragments their habitat and exposes them to greater predation. Scientists consider only 30% (17 of 57) of Canada’s boreal woodland caribou populations to be self-sustaining."[3][4] Additionally, it was observed that the caribou “… are extremely sensitive to both natural (such as forest fires) and human disturbances, and to habitat damage and fragmentation brought about by resource exploration, road building, and other human activities. New forest growth (following destruction of vegetation) provides habitat and food for other ungulates, which in turn attracts more predators, putting pressure on woodland caribou."[11]

Compared to barren-ground caribou of mainland Canada and Alaska (see Barren-ground caribou), boreal woodland caribou do not form large aggregations and are more dispersed, particularly at calving time. Their seasonal movements are not as extensive.[17] Mallory and Hillis explained how, "In North America, populations of the woodland caribou subspecies typically form small, isolated herds in winter, but are relatively sedentary, and migrate only short distances (50 – 150 km) during the rest of the year."[18]

- ^ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ Environment Canada 2012b.

- ^ a b Lunn 2013.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

davidsuzuki_2013_12was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gilbert, Ropiquet & Hassanin 2006.

- ^ Gillis 2013.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Benson_2011was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Geist 2007, p. 25.

- ^ Kavanagh, Maureen, ed. (2005) [1985], "Hinterland Who's Who", Canadian Wildlife Service/EC, ISBN 978-0-662-39659-8, archived from the original on 2013-12-24, retrieved 2013-12-21

- ^ Harding LE (2022) Available names for Rangifer (Mammalia, Artiodactyla, Cervidae) species and subspecies. ZooKeys 1119: 117-151. doi:10.3897/zookeys.1119.80233

- ^ a b "Boreal Caribou". Yellowknife, NT: Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society Northwest Territories Chapter. Retrieved 2013-12-19.

- ^ Canadian Forest Service 2000, p. 14.

- ^ Culling & Culling 2006, p. 1.

- ^ "Woodland caribou".

- ^ COSEWIC 2011, p. [page needed].

- ^ Environment Canada 2012b, p. 9.

- ^ Edmonds 1991.

- ^ Mallory & Hillis 1998, p. 49.

Cite error: There are <ref group=Notes> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=Notes}} template (see the help page).