Back الإبادة الجماعية في كمبوديا Arabic Kamboca soyqırımı Azerbaijani Геноцид в Камбоджа Bulgarian কম্বোডিয়ার গণহত্যা Bengali/Bangla Kambodžanski genocid BS Genocidi de Cambodja Catalan Kambodžská genocida Czech Genozid in Kambodscha German Γενοκτονία της Καμπότζης Greek Kamboĝa Genocido Esperanto

| Cambodian genocide | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War in Asia and the aftermath of the Cambodian Civil War | |

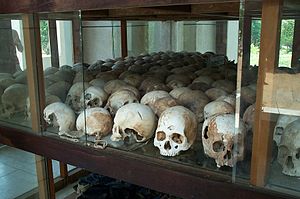

Skulls at the Choeung Ek memorial in Cambodia | |

| Location | Democratic Kampuchea (present-day Cambodia) |

| Date | 17 April 1975 – 7 January 1979 (3 years, 8 months and 20 days) |

| Target | Cambodia's previous military and political leadership, middle-class professionals, businesspeople, intellectuals, ethnic and religious minorities |

Attack type | Genocide, classicide, politicide, ethnic cleansing, cultural genocide, starvation, forced labour, torture, mass rape, summary execution |

| Deaths | 1.2 to 2.8 million[1] |

| Perpetrators | Khmer Rouge, Kampuchea Revolutionary Army |

| Defenders | Vietnam |

| Motive |

|

| History of Cambodia |

|---|

| Early history |

| Post-Angkor period |

| Colonial period |

| Independence and conflict |

| Peace process |

| Modern Cambodia |

| By topic |

|

|

The Cambodian genocide[a] was the systematic persecution and killing of Cambodian citizens[b] by the Khmer Rouge under the leadership of Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea, Pol Pot. It resulted in the deaths of 1.5 to 2 million people from 1975 to 1979, nearly 25% of Cambodia's population in 1975 (c. 7.8 million).[3][4]

Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge were supported for many years by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its chairman, Mao Zedong;[c] it is estimated that at least 90% of the foreign aid which the Khmer Rouge received came from China, including at least US$1 billion in interest-free economic and military aid in 1975 alone.[10][11][12] After it seized power in April 1975, the Khmer Rouge wanted to turn the country into an agrarian socialist republic, founded on the policies of ultra-Maoism and influenced by the Cultural Revolution.[d] Pol Pot and other Khmer Rouge officials met with Mao in Beijing in June 1975, receiving approval and advice, while high-ranking CCP officials such as Politburo Standing Committee member Zhang Chunqiao later visited Cambodia to offer help.[e] To fulfill its goals, the Khmer Rouge emptied the cities and frogmarched Cambodians to labor camps in the countryside, where mass executions, forced labor, physical abuse, torture, malnutrition, and disease were rampant.[17][18] In 1976, the Khmer Rouge renamed the country Democratic Kampuchea.

The massacres ended when the Vietnamese military invaded in 1978 and toppled the Khmer Rouge regime.[19] By January 1979, 1.5 to 2 million people had died due to the Khmer Rouge's policies, including 200,000–300,000 Chinese Cambodians, 90,000–500,000[f] Cambodian Cham (who are mostly Muslim),[23][24][25] and 20,000 Vietnamese Cambodians.[26][27] 20,000 people passed through the Security Prison 21, one of the 196 prisons the Khmer Rouge operated,[4][28] and only seven adults survived.[29] The prisoners were taken to the Killing Fields, where they were executed (often with pickaxes, to save bullets)[30] and buried in mass graves. Abduction and indoctrination of children was widespread, and many were persuaded or forced to commit atrocities.[31] As of 2009, the Documentation Center of Cambodia has mapped 23,745 mass graves containing approximately 1.3 million suspected victims of execution. Direct execution is believed to account for up to 60% of the genocide's death toll,[32] with other victims succumbing to starvation, exhaustion, or disease.

The genocide triggered a second outflow of refugees, many of whom escaped to neighboring Thailand and, to a lesser extent, Vietnam.[33] In 2003, by agreement[34] between the Cambodian government and the United Nations, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Court of Cambodia (Khmer Rouge Tribunal) were established to try the members of the Khmer Rouge leadership responsible for the Cambodian genocide. Trials began in 2009.[35] On 26 July 2010, the Trial Chamber convicted Kang Kek Iew for crimes against humanity and grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions. The Supreme Court Chamber increased his sentence to life imprisonment. Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were tried and convicted in 2014 of crimes against humanity and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions. On 28 March 2019, the Trial Chamber found Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan guilty of crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, and genocide of the Vietnamese ethnic, national and racial group. The Chamber additionally convicted Nuon Chea of genocide of the Cham ethnic and religious group under the doctrine of superior responsibility.[2] Both Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were sentenced to terms of life imprisonment.[36]

- ^ Heuveline, Patrick (2015). "The Boundaries of Genocide: Quantifying the Uncertainty of the Death Toll During the Pol Pot Regime (1975-1979)". Population Studies. 69 (2): 201–218. doi:10.1080/00324728.2015.1045546. PMC 4562795. PMID 26218856.

- ^ a b "Trial Chamber Summary of Judgement Case 002/02" (PDF). United Nations Office of Legal Affairs.

- ^

- Heuveline 2001, pp. 102–105: "As best as can now be estimated, over two million Cambodians died during the 1970s because of the political events of the decade, the vast majority of them during the mere four years of the 'Khmer Rouge' regime. This number of deaths is even more staggering when related to the size of the Cambodian population, then less than eight million. ... Subsequent reevaluations of the demographic data situated the death toll for the [civil war] in the order of 300,000 or less."

- Kiernan 2003b, pp. 586–587: "We may safely conclude, from known pre- and post-genocide population figures and from professional demographic calculations, that the 1975–79 death toll was between 1.671 and 1.871 million people, 21 to 24 percent of Cambodia's 1975 population."

- Sullivan, Meg (16 April 2015). "UCLA demographer produces best estimate yet of Cambodia's death toll under Pol Pot". UCLA. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- Tyner, James A.; Molana, Hanieh Haji (1 March 2020). "Ideologies of Khmer Rouge Family Policy: Contextualizing Sexual and Gender-Based Violence during the Cambodian Genocide". Genocide Studies International. 13 (2): 168–189. doi:10.3138/gsi.13.2.03. ISSN 2291-1847. S2CID 216505042. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Locardwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Chandler, David P. (2018). Brother Number One: A Political Biography of Pol Pot. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4299-8161-6.

- ^ Strangio, Sebastian (16 May 2012). "China's Aid Emboldens Cambodia". Yale University. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ a b c "The Chinese Communist Party's Relationship with the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s: An Ideological Victory and a Strategic Failure". Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. 13 December 2018. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Hood, Steven J. (1990). "Beijing's Cambodia Gamble and the Prospects for Peace in Indochina: The Khmer Rouge or Sihanouk?". Asian Survey. 30 (10): 977–991. doi:10.2307/2644784. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2644784.

- ^ a b "China-Cambodia Relations". Radio Free Asia. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ a b Levin, Dan (30 March 2015). "China Is Urged to Confront Its Own History". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Kiernan, Ben (2008). The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia Under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–79. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-3001-4299-0.

- ^ Laura, Southgate (2019). ASEAN Resistance to Sovereignty Violation: Interests, Balancing and the Role of the Vanguard State. Policy Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-5292-0221-2.

- ^ Jackson, Karl D (1989). Cambodia, 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-6910-2541-4.

- ^ Ervin Staub. The roots of evil: the origins of genocide and other group violence. Cambridge University Press, 1989. p. 202

- ^ David Chandler & Ben Kiernan, ed. (1983). Revolution and its Aftermath. New Haven: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies. ISBN 978-0-9386-9205-8.

- ^ Wang, Youqin. "2016: 张春桥幽灵" (PDF) (in Chinese). The University of Chicago. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Etcheson 2005, p. 119.

- ^ Heuveline 1998, pp. 49–65.

- ^ Mayersan 2013, p. 182.

- ^ Ben Kiernan, Wendy Lower, Norman Naimark, Scott Straus et al. The Cambridge World History of Genocide: Volume 3. Genocide in the Contemporary Era, 1914–2020. Cambridge University Press, 2023. [1]

- ^ Kiernan 2003b.

- ^ Bruckmayr, Philipp (1 July 2006). "The Cham Muslims of Cambodia: From Forgotten Minority to Focal Point of Islamic Internationalism". American Journal of Islam and Society. 23 (3): 1–23. doi:10.35632/ajis.v23i3.441.

- ^ "Cambodia: Holocaust and Genocide Studies". College of Liberal Arts. University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Genocide in Cambodia". Holocaust Memorial Day Trust. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Genocide in Cambodia". Holocaust Museum Houston. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:8was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Zhang, Zhifeng (25 April 2014). 华侨忆红色高棉屠杀:有文化的华人必死. Renmin Wang (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ "Mapping the Killing Fields". Documentation Center of Cambodia. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

Through interviews and physical exploration, DC-Cam identified 19,733 mass burial pits, 196 prisons that operated during the Democratic Kampuchea (DK) period, and 81 memorials constructed by survivors of the DK regime.

- ^ Kiernan, Ben (2014). The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia Under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–79. Yale University Press. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-3001-4299-0.

Like all but seven of the twenty thousand Tuol Sleng prisoners, she was murdered anyway.

- ^ Landsiedel, Peter, "The Killing Fields: Genocide in Cambodia" Archived 21 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, P&E World Tour, 27 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2019

- ^ Southerland, D. (20 July 2006). "Cambodia Diary 6: Child Soldiers – Driven by Fear and Hate". Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Seybolt, Aronson & Fischoff 2013, p. 238.

- ^ State of the World's Refugees, 2000 Archived 17 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, p. 92. Retrieved 21 January 2019

- ^ "Agreement between the United Nations and the Royal Government of Cambodia concerning the prosecution under Cambodian law of crimes committed during the period of Democratic Kampuchea". United Nations Assistance to the Khmer Rouge Trials. 11 April 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ Mendes 2011, p. 13.

- ^ "Judgement in Case 002/01 to be pronounced on 7 August 2014 | Drupal". www.eccc.gov.kh. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).