| Chlamydiota | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Superphylum: | PVC superphylum |

| Phylum: | Chlamydiota Garrity & Holt 2021[3] |

| Class: | Chlamydiia Horn 2016[1][2] |

| Orders and families | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Chlamydiota (synonym Chlamydiae) are a bacterial phylum and class whose members are remarkably diverse, including pathogens of humans and animals, symbionts of ubiquitous protozoa,[4] and marine sediment forms not yet well understood.[5] All of the Chlamydiota that humans have known about for many decades are obligate intracellular bacteria; in 2020 many additional Chlamydiota were discovered in ocean-floor environments, and it is not yet known whether they all have hosts.[5] Historically it was believed that all Chlamydiota had a peptidoglycan-free cell wall, but studies in the 2010s demonstrated a detectable presence of peptidoglycan, as well as other important proteins.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

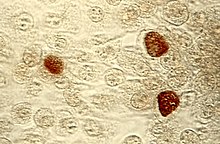

Among the Chlamydiota, all of the ones long known to science grow only by infecting eukaryotic host cells. They are as small as or smaller than many viruses. They are ovoid in shape and stain Gram-negative. They are dependent on replication inside the host cells; thus, some species are termed obligate intracellular pathogens and others are symbionts of ubiquitous protozoa. Most intracellular Chlamydiota are located in an inclusion body or vacuole. Outside cells, they survive only as an extracellular infectious form.

These Chlamydiota can grow only where their host cells grow, and develop according to a characteristic biphasic developmental cycle.[12][13][14] Therefore, clinically relevant Chlamydiota cannot be propagated in bacterial culture media in the clinical laboratory. They are most successfully isolated while still inside their host cells.

Of various Chlamydiota that cause human disease, the two most important species are Chlamydia pneumoniae, which causes a type of pneumonia, and Chlamydia trachomatis, which causes chlamydia. Chlamydia is the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the United States, and 2.86 million chlamydia infections are reported annually.

- ^ Horn M. (2010). "Class I. Chlamydiia class. nov.". In Krieg NR, Staley JT, Brown DR, Hedlund BP, Paster BJ, Ward NL, Ludwig W, Whitman WB. (eds.). Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. p. 844. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-68572-4. ISBN 978-0-387-95042-6.

- ^ Oren A, Garrity GM. (2016). "Validation list no. 170. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published". Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 66 (7): 2463–2466. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.001149. PMID 27530111.

- ^ Oren A, Garrity GM (2021). "Valid publication of the names of forty-two phyla of prokaryotes". Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 71 (10): 5056. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.005056. PMID 34694987. S2CID 239887308.

- ^ Sixt BS, Siegl A, Müller C, Watzka M, Wultsch A, Tziotis D, et al. (2013). "Metabolic features of Protochlamydia amoebophila elementary bodies—a link between activity and infectivity in Chlamydiae". PLOS Pathogens. 9 (8): e1003553. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003553. PMC 3738481. PMID 23950718.

- ^ a b Dharamshi JE, Tamarit D, Eme L, Stairs CW, Martijn J, Homa F, et al. (March 2020). "Marine Sediments Illuminate Chlamydiae Diversity and Evolution". Current Biology. 30 (6): 1032–1048.e7. Bibcode:2020CBio...30E1032D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.02.016. PMID 32142706. S2CID 212423997.

- ^ Pilhofer M, Aistleitner K, Biboy J, Gray J, Kuru E, Hall E, et al. (2013-12-02). "Discovery of chlamydial peptidoglycan reveals bacteria with murein sacculi but without FtsZ". Nature Communications. 4 (1): 2856. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2856P. doi:10.1038/ncomms3856. PMC 3847603. PMID 24292151.

- ^ Jacquier N, Viollier PH, Greub G (March 2015). "The role of peptidoglycan in chlamydial cell division: towards resolving the chlamydial anomaly". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 39 (2): 262–275. doi:10.1093/femsre/fuv001. PMID 25670734.

- ^ Malhotra M, Sood S, Mukherjee A, Muralidhar S, Bala M (September 2013). "Genital Chlamydia trachomatis: an update". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 138 (3): 303–316. PMC 3818592. PMID 24135174.

- ^ Liechti GW, Kuru E, Hall E, Kalinda A, Brun YV, VanNieuwenhze M, Maurelli AT (February 2014). "A new metabolic cell-wall labelling method reveals peptidoglycan in Chlamydia trachomatis". Nature. 506 (7489): 507–510. Bibcode:2014Natur.506..507L. doi:10.1038/nature12892. PMC 3997218. PMID 24336210.

- ^ Liechti G, Kuru E, Packiam M, Hsu YP, Tekkam S, Hall E, et al. (May 2016). "Pathogenic Chlamydia Lack a Classical Sacculus but Synthesize a Narrow, Mid-cell Peptidoglycan Ring, Regulated by MreB, for Cell Division". PLOS Pathogens. 12 (5): e1005590. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005590. PMC 4856321. PMID 27144308.

- ^ Gupta RS (August 2011). "Origin of diderm (Gram-negative) bacteria: antibiotic selection pressure rather than endosymbiosis likely led to the evolution of bacterial cells with two membranes". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 100 (2): 171–182. doi:10.1007/s10482-011-9616-8. PMC 3133647. PMID 21717204.

- ^ Horn M (2008). "Chlamydiae as symbionts in eukaryotes". Annual Review of Microbiology. 62: 113–131. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162818. PMID 18473699. S2CID 13405815.

- ^ Abdelrahman YM, Belland RJ (November 2005). "The chlamydial developmental cycle". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 29 (5): 949–959. doi:10.1016/j.femsre.2005.03.002. PMID 16043254.

- ^ Horn M, Collingro A, Schmitz-Esser S, Beier CL, Purkhold U, Fartmann B, et al. (April 2004). "Illuminating the evolutionary history of Chlamydiae". Science. 304 (5671): 728–730. Bibcode:2004Sci...304..728H. doi:10.1126/science.1096330. PMID 15073324. S2CID 39036549.