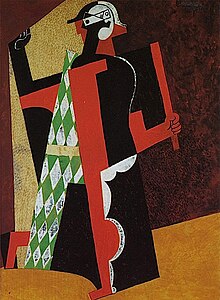

Crystal Cubism (French: Cubisme cristal or Cubisme de cristal) is a distilled form of Cubism consistent with a shift, between 1915 and 1916, towards a strong emphasis on flat surface activity and large overlapping geometric planes. The primacy of the underlying geometric structure, rooted in the abstract, controls practically all of the elements of the artwork.[1]

This range of styles of painting and sculpture, especially significant between 1917 and 1920 (referred to alternatively as the Crystal Period, classical Cubism, pure Cubism, advanced Cubism, late Cubism, synthetic Cubism, or the second phase of Cubism), was practiced in varying degrees by a multitude of artists; particularly those under contract with the art dealer and collector Léonce Rosenberg—Jean Metzinger, Juan Gris, Albert Gleizes, Henri Laurens, and Jacques Lipchitz most noticeably of all. The tightening of the compositions, the clarity and sense of order reflected in these works, led to its being referred to by the French poet and art critic Maurice Raynal as 'crystal' Cubism.[2] Considerations manifested by Cubists prior to the outset of World War I—such as the fourth dimension, dynamism of modern life, the occult, and Henri Bergson's concept of duration—had now been vacated, replaced by a purely formal frame of reference that proceeded from a cohesive stance toward art and life.

As post-war reconstruction began, so too did a series of exhibitions at Léonce Rosenberg's Galerie de L'Effort Moderne: order and the allegiance to the aesthetically pure remained the prevailing tendency. The collective phenomenon of Cubism once again—now in its advanced revisionist form—became part of a widely discussed development in French culture. Crystal Cubism was the culmination of a continuous narrowing of scope in the name of a return to order; based upon the observation of the artists relation to nature, rather than on the nature of reality itself.[3]

Crystal Cubism, and its associative rappel à l’ordre, has been linked with an inclination—by those who served the armed forces and by those who remained in the civilian sector—to escape the realities of the Great War, both during and directly following the conflict. The purifying of Cubism from 1914 through the mid-1920s, with its cohesive unity and voluntary constraints, has been linked to a much broader ideological transformation towards conservatism in both French society and French culture. In terms of the separation of culture and life, the Crystal Cubist period emerges as the most important in the history of Modernism.[1]

- ^ a b Christopher Green, Cubism and its Enemies, Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–1928, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1987, pp. 13-47, 215

- ^ Christopher Green, Late Cubism, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ^ Thomas Vargish, Delo E. Mook, Inside Modernism: Relativity Theory, Cubism, Narrative, Yale University Press, 1999, p. 88, ISBN 0300076134