Back تدريس متمايز Arabic Instrucció diferenciada Catalan Differenzierung (Didaktik) German Instrucción diferenciada Spanish Pédagogie différenciée French הוראה דיפרנציאלית HE Pembelajaran berdiferensiasi ID Differentiatie (onderwijs) Dutch Mësimi i diferencuar Albanian Диференцијација наставе Serbian

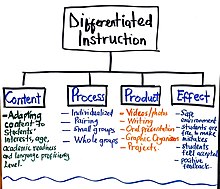

Differentiated instruction and assessment, also known as differentiated learning or, in education, simply, differentiation, is a framework or philosophy for effective teaching that involves providing all students within their diverse classroom community of learners a range of different avenues for understanding new information (often in the same classroom) in terms of: acquiring content; processing, constructing, or making sense of ideas; and developing teaching materials and assessment measures so that all students within a classroom can learn effectively, regardless of differences in their ability.[1] Differentiated instruction means using different tools, content, and due process in order to successfully reach all individuals. Differentiated instruction, according to Carol Ann Tomlinson,[2] is the process of "ensuring that what a student learns, how he or she learns it, and how the student demonstrates what he or she has learned is a match for that student's readiness level, interests, and preferred mode of learning."[3] According to Boelens et al. (2018), differentiation can be on two different levels: the administration level and the classroom level. The administration level takes the socioeconomic status and gender of students into consideration. At the classroom level, differentiation revolves around content, processing, product, and effects. On the content level, teachers adapt what they are teaching to meet the needs of students. This can mean making content more challenging or simplified for students based on their levels. The process of learning can be differentiated as well. Teachers may choose to teach individually at a time, assign problems to small groups, partners or the whole group depending on the needs of the students. By differentiating product, teachers decide how students will present what they have learned. This may take the form of videos, graphic organizers, photo presentations, writing, and oral presentations. All these take place in a safe classroom environment where students feel respected and valued—effects.[4]

When language is the factor for differentiation, Echevarria et al. (2017), proponents of the Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOP) strongly supports and guides teachers to differentiate instruction to English as a Second Language Learners (ELLs) who have a range of learning ability levels—beginning, intermediate and advanced. Here, differentiated instruction will mean adapting a whole new instructional strategy that a teacher of a typical classroom of native speakers of English would not have a need to.[5]

Differentiated classrooms have also been described as ones that respond to student variety in readiness levels, interests, and learning profiles. It is a classroom that includes and allows all students to be successful. To do this, a teacher sets different expectations for task completion for students, specifically based upon their individual needs.[6] Teachers can differentiate in four ways: 1) through content, 2) process, 3) product, and 4) learning environment based on the individual learner.[7] Differentiation stems from beliefs about differences among learners, how they learn, learning preferences, and individual interests (Algozzine & Anderson, 2007). Therefore, differentiation is an organized, yet flexible way of proactively adjusting teaching and learning methods to accommodate each child's learning needs and preferences to achieve maximum growth as a learner.[8]

- ^ Tomlinson, Carol (2001). How to Differentiate Instruction in Mixed-Ability Classrooms (2 ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. ISBN 978-0871205124.

- ^ Tomlinson, Carol Ann (2004-06-01). "Point/counterpoint". Roeper Review. 26 (4): 188–189. doi:10.1080/02783190409554268. ISSN 0278-3193. S2CID 219711221.

- ^ Rock, Marcia L.; Gregg, Madeleine; Ellis, Edwin; Gable, Robert A. (2008-01-01). "REACH: A Framework for Differentiating Classroom Instruction" (PDF). Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth. 52 (2): 31–47. doi:10.3200/PSFL.52.2.31-47. ISSN 1045-988X. S2CID 144948134.

- ^ Boelens, Ruth; Voet, Michiel; De Wever, Bram (2018-05-01). "The design of blended learning in response to student diversity in higher education: Instructors' views and use of differentiated instruction in blended learning". Computers & Education. 120: 197–212. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2018.02.009. hdl:1854/LU-8550786. ISSN 0360-1315.

- ^ Echevarría, Vogt & Short, J; Vogt, M; Short, D (2017). Making content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP model (5th ed.). Pearson.

- ^ Lawrence-Brown, Diana (2004). "Differentiated Instruction: Inclusive Strategies for Standards-Based Learning That Benefit The Whole Class". American Secondary Education. 32 (3): 34–62. JSTOR 41064522. ProQuest 195190361.

- ^ Ministry of Education. (2007). Differentiated instruction teacher's guide: Getting to the core of teaching and learning. Toronto: Queen's Printer for Ontario.

- ^ Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. New Jersey: Pearson Education.