Back Cuarenta acres y una mula Spanish 40 acres et une mule French 40 אקרים ופרד HE 40 acri e un mulo Italian 40エーカーとラバ1頭 Japanese

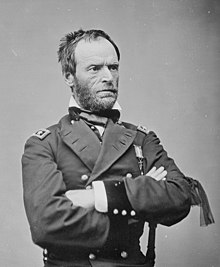

Forty acres and a mule refers to a key part of Special Field Orders, No. 15 (series 1865), a wartime order proclaimed by Union General William Tecumseh Sherman on January 16th, 1865, during the American Civil War, to allot land to some freed families, in plots of land no larger than 40 acres (16 ha).[1] Sherman later ordered the army to lend mules for the agrarian reform effort. The field orders followed a series of conversations between Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Radical Republican abolitionists Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens[2] following disruptions to the institution of slavery provoked by the American Civil War. They provided for the confiscation of 400,000 acres (160,000 ha) of land along the Atlantic coast of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida and the dividing of it into parcels of not more than 40 acres (16 ha),[3] on which were to be settled approximately 18,000 formerly enslaved families and other black people then living in the area.

Many freed people believed, after being told by various political figures, that they had a right to own the land they had been forced to work as slaves and were eager to control their own property. Freed people widely expected to legally claim 40 acres of land.[4] However, Abraham Lincoln's successor as president, Andrew Johnson, tried to reverse the intent of Sherman's wartime Order No. 15 and similar provisions included in the second Freedmen's Bureau bills.

Some land redistribution occurred under military jurisdiction during the war and for a brief period thereafter. However, federal and state policy during the Reconstruction era emphasized wage labor, not land ownership, for black people. Almost all land allocated during the war was restored to its pre-war white owners.[5] Several black communities did maintain control of their land, and some families obtained new land by homesteading. Black land ownership increased markedly in Mississippi during the 19th century, particularly. The state had much undeveloped bottomland (low-lying alluvial land near a river) behind riverfront areas that had been cultivated before the war. Most black people acquired land through private transactions, with ownership peaking at 15 million acres (6.1 million hectares) or ~23,000 square miles in 1910, before an extended financial recession caused problems that resulted in the loss of property for many.[citation needed] Women were never given forty acres since women still could not own property.

- ^ Order by the Commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gateswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ O.R. Series 1, Volume 47, Part 2, 60-62

- ^ Foner, Eric (2014). Reconstruction: America's unfinished revolution, 1863–1877. Harper. ISBN 978-0062035868. OCLC 877900566.[page needed]

- ^ fultonk (6 January 2013). "The Truth Behind '40 Acres and a Mule' | African American History Blog". The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross. Retrieved 20 October 2024.