Back جون روس Arabic جون روس ARZ Con Ross (çeroki) Azerbaijani John Ross Catalan John Ross (cherokeehøvding) Danish John Ross (Häuptling) German John Ross Spanish John Ross (chef cherokee) French John Ross Galician John Ross (capo indiano) Italian

John Ross | |

|---|---|

| Koo-wis-gu-wi | |

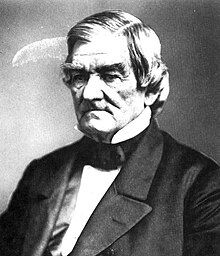

John Ross ca. 1866 | |

| Cherokee Nation Principal Chief | |

| In office 1828–1862 | |

| Preceded by | William Hicks |

| Succeeded by | William P. Ross |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 3, 1790 Turkeytown, Alabama |

| Died | August 1, 1866 (aged 75) Washington, D.C. |

| Resting place | Ross Cemetery, Cherokee County, Oklahoma |

| Spouse(s) | Quatie Brown Henley (c. 1790–1839) Mary Brian Stapler (1826–1865) |

| Relations | Great-granddaughter Mary G. Ross; Nephew William P. Ross; Niece Mary Jane (Ross) Ross |

| Children | 7 |

| Known for | opposition to Treaty of New Echota; Trail of Tears; Union supporter during American Civil War |

John Ross (Cherokee: ᎫᏫᏍᎫᏫ, romanized: Guwisguwi, lit. 'Mysterious Little White Bird'; October 3, 1790 – August 1, 1866) was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1828 to 1866; he served longer in that position than any other person. Ross led the nation through such tumultuous events as forced removal to Indian Territory and the American Civil War.

Ross was the son of a Cherokee mother and a Scottish father. His mother and maternal grandmother were each of mixed Scots-Cherokee ancestry but brought up in Cherokee culture, and his maternal grandfather was a Scottish immigrant. The Cherokee culture was and still is clan-based and is matrilineal, meaning that a Cherokee inherits their clan affiliation from the mother, and all men in a child’s clan are termed Uncle. Cherokee don’t marry within the same clan. The father fulfills responsibilities to provide for and to be part of the family unit with his wife and Children.

The Cherokee absorbed bicultural descendants into their culture and, by the time of Ross and Ridge, had what could be described as a mixed culture based on traditional Cherokee values but which deeply integrated other cultures, too. As a result, as young John was raised as Cherokee within a high social order, learning about colonial British society was an inherently Cherokee value. As an educated and socially prominent Cherokee, he was bilingual and bicultural. His parents sent him for formal schooling to institutions that served other bicultural Cherokee people. And while non-Native historians have fixated on his blood quantum of one-eighth Cherokee was less than most prominent Cherokees of his time, he was an accepted and effective leader among his people.

At the age of twenty, Ross was appointed as a US Indian agent in 1811. During the War of 1812, he served as adjutant of a Cherokee regiment under the command of Andrew Jackson. After the end of the Red Stick War (which was effectively a civil war among the Creek), Ross started a tobacco plantation in Tennessee. In 1816, he built a warehouse and trading post on the Tennessee River north of the mouth of Chattanooga Creek, and started a ferry service that carried passengers from the south side of the river (Cherokee Nation) to the north side (USA). His businesses served as the start of a community known as Ross's Landing on the Tennessee River (now Chattanooga, Tennessee). Concurrently, Ross developed a keen interest in Cherokee politics and attracted the attention of the Cherokee elders, especially Principal Chiefs Pathkiller and Charles R. Hicks. Together with Major Ridge, they became his political mentors.

Ross first went to Washington, DC, in 1816 as part of a Cherokee delegation to negotiate issues of national boundaries, land ownership, and white encroachment. As the only delegate fluent in English, Ross became the principal negotiator despite his relative youth. When he returned to the Cherokee Nation in 1817, he was elected to the National Council. He became council president in the following year. The majority of the council were men like Ross: wealthy, educated, English-speaking, and of mixed blood. Even the traditionalist full-blood Cherokee perceived that he had the skills necessary to contest the whites' demands that the Cherokee cede their land and move beyond the Mississippi River. In that position, Ross's first action was to reject an offer of $200,000 from the US Indian agent made for the Cherokee to relocate voluntarily. Thereafter Ross made more trips to Washington, even as white demands intensified. In 1824, Ross boldly petitioned Congress for redress of Cherokee grievances, which made the Cherokee the first tribe ever to do so. Along the way, Ross built political support in the US capital for the Cherokee cause.

Both Pathkiller and Charles R. Hicks died in January 1827. Hicks's brother, William, was appointed interim chief. Ross and Major Ridge shared responsibilities for the affairs of the tribe. Because William did not impress the Cherokee as a leader, they elected Ross as permanent principal chief in October 1828, a position that he held until his death.

The problem of removal split the Cherokee Nation politically. Ross, backed by the vast majority, tried repeatedly to stop white political powers from forcing the nation to move. He led a faction that became known as the National Party. Twenty others, who came to believe that further resistance would be futile, wanted to seek the best settlement they could get and formed the "Treaty Party," or "Ridge Party," led by Major Ridge. Treaty Party negotiated with the United States and signed the Treaty of New Echota on December 29, 1835, which required the Cherokee to leave by 1838. Neither Chief Ross nor the national council ever approved this treaty, but the US government regarded it as valid. The majority, about two-thirds of Cherokee people, followed the National Party and objected to and voted against complying with the Treaty of New Echota.

Forced removal spared no one, including Principal Chief Ross, who lost his first wife Quatie (Brown) Ross during the Trail of Tears.[1]

Removal and the subsequent coordinated executions of Treaty Party signers Major Ridge, John Ridge, and former editor of the Cherokee Phoenix Elias Boudinot on June 22, 1839 thrust the Cherokee Nation into a civil war. Despite the Act of Union signed by Old Settlers, (Cherokees who removed west earlier under the Treaties of 1817 and 1819) and the Eastern Emigrants (those forced to remove under Ross's leadership) on July 12, 1839 and the new Cherokee Constitution that followed August 23, 1839, violent reprisals continued through 1846.[2]

Cherokee people continued to elect Ross as Principal Chief through the Civil War Era. Ross hoped to maintain neutrality during the Civil War, but a variety of conditions prevented him from doing so. First, Stand Watie, a political opponent, Treaty Party member, kin to the Ridges, and Boudinot's brother raised a regiment on behalf of the Confederate army. Second, surrounding states seceded. Third, surrounding Native nations signed treaties with the confederacy. And finally, federal troops abandoned the Indian Territory, leaving the Nation to defend itself in violation of treaty commitments. Rather than see the Cherokee Nation divided against itself again, Ross, with the consent of council, signed a treaty with the Confederacy.[3]

For the Cherokee Nation, the Civil War represented the extended divisions created by Removal and the Trail of Tears. Ross supporters largely served under John Drew's regiment. Treaty Party supporters largely served under Stand Watie. During the war, federal troops arrested Ross and removed him from Indian Territory. Many Cherokee people less committed to the Confederacy and more committed to the Cherokee Nation refused to engage in battles against other Native peoples, including those Muscogee Creek people under Opothleyahola seeking refuge in Kansas.[4]

Once outside the Indian Territory, Ross negotiated agreements with the Union for Cherokee support through Indian Home Guard Regiments.[5] Many of those formerly fighting for the Confederacy but loyal to Ross, switched sides to support the Union through the Indian Home Guard.

Ross's absence from Indian Territory provided a political opening for Watie. While Ross was away, those loyal to Watie elected him Principal Chief. When Ross returned, an election was held re-electing him to the office. At those close of the war, those calling themselves the Southern Cherokees under Watie's leadership stepped forward as the rightful negotiators of any treaty, as did Ross as the elected chief.

The US required the Five Civilized Tribes to negotiate new peace treaties after the war. Ross made another trip to Washington, DC, for this purpose. Although Ross had negotiated with Lincoln during the war, his assassination enabled US commissioners to treat the Cherokee Nation as a defeated enemy. As Ross had feared, commissioners used the political divisions to extract greater penalties from the Cherokee Nation. Despite these setbacks, Ross worked to re-establish a unified Cherokee Nation and re-establish a nation-to-nation treaty with the US. He died in Washington, DC on August 1, 1866.

- ^ Perdue, Theda; Green, Michael D. (2007). The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears. The Penguin library of American Indian history. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-03150-4.

- ^ McLoughlin, William Gerald (1993). After the Trail of Tears: the Cherokees' struggle for sovereignty, 1839-1880. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2111-4.

- ^ Confer, Clarissa W. (2007). The Cherokee nation in the Civil War. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3803-9.

- ^ Confer, Clarissa W. (2007). The Cherokee nation in the Civil War. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3803-9.

- ^ MacLoughlin, William Gerald (1994). After the trail of tears: the Cherokees' struggle for sovereignty, 1839–1880 (2. Aufl. ed.). Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2111-4.