Back Farao Afrikaans Pharao ALS ፈርዖን Amharic Fero ANN فرعون Arabic فرعون ARZ ফাৰাও Assamese Faraón AST Firon Azerbaijani Фирғәүен Bashkir

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |

|---|---|

| |

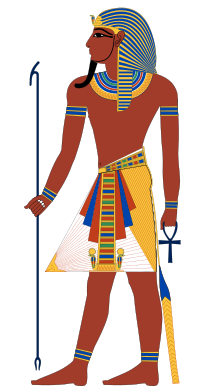

A typical depiction of a pharaoh usually depicted the king wearing the nemes headdress, a false beard, and an ornate shendyt (kilt) (after Djoser of the Third Dynasty) | |

| Details | |

| Style | Five-name titulary |

| First monarch |

|

| Last monarch |

|

| Formation |

|

| Abolition |

|

| Residence | Varies by era |

| Appointer | Hereditary |

| ||

| pr-ˤ3 "Great house" in hieroglyphs | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| nswt-bjt "King of Upper and Lower Egypt" in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pharaoh (/ˈfɛəroʊ/, US also /ˈfeɪ.roʊ/;[4] Egyptian: pr ꜥꜣ;[note 1] Coptic: ⲡⲣ̄ⲣⲟ, romanized: Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: פַּרְעֹה Parʿō)[5] is the vernacular term often used for the monarchs of ancient Egypt, who ruled from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BCE) until the annexation of Egypt by the Roman Republic in 30 BCE.[6] However, regardless of gender, "king" was the term used most frequently by the ancient Egyptians for their monarchs through the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty during the New Kingdom. The earliest confirmed instances of "pharaoh" used contemporaneously for a ruler were a letter to Akhenaten (reigned c. 1353–1336 BCE) or an inscription possibly referring to Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BCE).

In the early dynasties, ancient Egyptian kings had as many as three titles: the Horus, the Sedge and Bee (nswt-bjtj), and the Two Ladies or Nebty (nbtj) name.[7] The Golden Horus and the nomen and prenomen titles were added later.[8]

In Egyptian society, religion was central to everyday life. One of the roles of the king was as an intermediary between the deities and the people. The king thus was deputised for the deities in a role that was both as civil and religious administrator. The king owned all of the land in Egypt, enacted laws, collected taxes, and served as commander-in-chief of the military.[9] Religiously, the king officiated over religious ceremonies and chose the sites of new temples. The king was responsible for maintaining Maat (mꜣꜥt), or cosmic order, balance, and justice, and part of this included going to war when necessary to defend the country or attacking others when it was believed that this would contribute to Maat, such as to obtain resources.[10]

During the early days prior to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Deshret or the "Red Crown", was a representation of the kingdom of Lower Egypt,[11] while the Hedjet, the "White Crown", was worn by the kings of Upper Egypt.[12] After the unification of both kingdoms, the Pschent, the combination of both the red and white crowns became the official crown of the pharaoh.[13] With time new headdresses were introduced during different dynasties such as the Khat, Nemes, Atef, Hemhem crown, and Khepresh. At times, a combination of these headdresses or crowns worn together was depicted.

- ^ a b Clayton 1995, p. 217. "Although paying lip-service to the old ideas and religion, in varying degrees, pharaonic Egypt had in effect died with the last native pharaoh, Nectanebo II in 343 BCE."

- ^ Tyldesley, Joyce (2009). Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt. Profile Books. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1861979018.

The Ptolemies believed themselves to be a valid Egyptian dynasty, and devoted a great deal of time and money to demonstrating that they were the theological continuation of all the dynasties that had gone before. Cleopatra defined herself as an Egyptian queen, and drew on the iconography and cultural references of earlier queens to reinforce her position. Her people and her contemporaries accepted her as such.

- ^ von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Verlag Philipp von Zabern. pp. 266–267. ISBN 978-3422008328.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1405881180

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew Concordance – 6547. Paroh". Bible Hub. Archived from the original on 2022-10-18. Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs the Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson, CE 2012. Print.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (2002). Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-66420-7.

- ^ Bierbrier, Morris L. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6250-0.

- ^ "Pharaoh". AncientEgypt.co.uk. The British Museum. 1999. Archived from the original on 27 November 1999. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Mark, Joshua (2 September 2009). "Pharaoh – World History Encyclopedia". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Hagen, Rose-Marie; Hagen, Rainer (2007). Egypt Art. New Holland Publishers Pty, Ltd. ISBN 978-3-8228-5458-7.

- ^ "The royal crowns of Egypt". Egypt Exploration Society. 7 March 2019. Archived from the original on 2022-05-18. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ Gaskell, G. (2016). A Dictionary of the Sacred Language of All Scriptures and Myths. Routledge Revivals. ISBN 978-1-317-58942-6.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).