Back صوت واحد قابل للتحويل Arabic Votu únicu tresferible AST Vot únic transferible Catalan Systém jednoho přenosného hlasu Czech Pleidlais sengl drosglwyddadwy Welsh Übertragbare Einzelstimmgebung German Μεταφερόμενη μονοσταυρία Greek Unuopa transdonebla voĉdono Esperanto Voto único transferible Spanish تکرأی انتقالپذیر Persian

| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

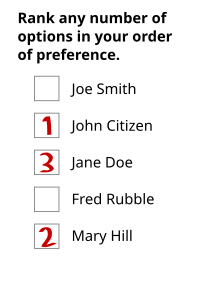

The single transferable vote (STV) or proportional-ranked choice voting (P-RCV)[a] is a multi-winner electoral system in which each voter casts a single vote in the form of a ranked ballot. Voters have the option to rank candidates, and their vote may be transferred according to alternative preferences if their preferred candidate is eliminated or elected with surplus votes, so that their vote is used to elect someone they prefer over others in the running. STV aims to approach proportional representation based on votes cast in the district where it is used, so that each vote is worth about the same as another.

STV is a family of proportional multi-winner electoral systems whose results are equivalent to those produced by proportional representation election systems based on lists. STV systems can be thought of as a variation on the largest remainders method that uses candidate-based solid coalitions, rather than party lists.[clarification needed][1] Surplus votes belonging to winning candidates (those in excess of an electoral quota) may be thought of as remainder votes. As a remainder under the largest remainder system, they are used to possibly obtain another seat for the party. As a remainder under STV, they are transferred to a voter's subsequent preferences if necessary, and thus a vote may be transferred across party lines, to a candidate on a different party slate, if that is how the voter marked their preferences.

Under STV, no one party or voting bloc can take all the seats in a district unless the number of seats in the district is very small or almost all the votes cast are cast for one party's candidates (which is seldom the case). This makes it different from other commonly used candidate-based systems. In winner-take-all or plurality systems – such as first-past-the-post (FPTP), instant-runoff voting (IRV), and block voting – one party or voting bloc can take all seats in a district.

The key to STV's approximation of proportionality is that each voter effectively only casts a single vote in a district contest electing multiple winners, while the ranked ballots (and sufficiently large districts) allow the results to achieve a high degree of proportionality with respect to partisan affiliation within the district, as well as representation by gender and other descriptive characteristics. The use of a quota means that, for the most part, each successful candidate is elected with the same number of votes. This equality produces fairness in the particular sense that a party taking twice as many votes as another party will generally take twice the number of seats compared to that other party.

Under STV, winners are elected in a multi-member constituency (district) or at-large, also in a multiple-winner contest. Every sizeable group within the district wins at least one seat: the more seats the district has, the smaller the size of the group needed to elect a member. In this way, STV provides approximately proportional representation overall, ensuring that substantial minority factions have some representation.

There are several STV variants. Two common distinguishing characteristics are whether or not ticket voting is allowed and the manner in which surplus votes are transferred. In Australia, lower house elections do not allow ticket voting; some but not all state upper house systems do allow ticket voting. In Ireland and Malta, surplus votes are transferred as whole votes (there may be some randomness) and neither allows ticket voting. In Hare–Clark, used in Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory, there is no ticket voting and surplus votes are fractionally transferred based on the last parcel of votes received by winners in accordance with the Gregory method.[2][3][4] Systems that use the Gregory method for surplus vote transfers are strictly non-random. Other distinguishing features include District Magnitude (number of members in the district) (with all districts having the same DM or varying DM), how to fill casual vacancies (by-elections or other), and the number of preferences that the voter must mark (optional-preferential voting or other).[5]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Gallagher, Michael (1992). "Comparing Proportional Representation Electoral Systems: Quotas, Thresholds, Paradoxes and Majorities". British Journal of Political Science. 22 (4): 469–496. doi:10.1017/S0007123400006499. ISSN 0007-1234. JSTOR 194023.

- ^ Terry Newman, Hare-Clark in Tasmania

- ^ George Howatt, Democratic Representation under the Hare-Clark System – The Need for Seven-Member Electorates

- ^ Farrell and McAllister (2006). The Australian Electoral System. UNSW Press. pp. 58–61.

- ^ Farell and McAllister. The Australian Electoral System. p. 60.