Back Popular crusades English جنگهای صلیبی مردمی Persian Croisades populaires French Crociata popolare Italian Volkskruistochten Dutch

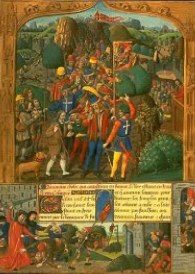

São denominadas como cruzadas populares, os vários movimentos inspirados nas pregações favoráveis às cruzadas, mas que não foram oficialmente sancionados pela Igreja Católica. Tais movimentos diferem das "cruzadas oficiais" autorizadas pelo papado que eram formadas por exércitos liderados pelos nobres, que recebiam a benção do Papa, enquanto que as cruzadas populares eram geralmente desorganizadas e formadas, em sua maioria, por contingentes de camponeses mal armados, às vezes, liderados por pessoas da baixa nobreza e com pequenos contingentes de cavalaria[1] [2].

Dentre tais movimentos, podem-se mencionar:

- A Cruzada Popular de 1096;

- A Cruzada das Crianças (1212)

- A Cruzada dos Pastores de 1251[3] [4];

- A Cruzada dos Pobres (1309)[5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] e;

- A Cruzada dos Pastores de 1320[13] [14] [15] [16];

Referências

- ↑ Gary Dickson, "Popular Crusades and Children's Crusade", in André Vauchez (ed.), Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages (James Clarke & Co., 2002.

- ↑ Giles Constable, "The Historiography of the Crusades", in Angeliki E. Laiou and Roy Parviz Mottahedeh (eds.), The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World (Dumbarton Oaks, 2001).

- ↑ Pages 226-227 d'un ouvrage consultable en ligne, em francês, acesso em 26/07/2021

- ↑ Voir Jacques Le Goff, Saint Louis, Gallimard, 1996, p. 189

- ↑ Peter Lock, "The Hospitaller Passagium and the Pastoreaux or Shepherds' Crusade, 1309", The Routledge Companion to the Crusades (Routledge, 2006), pp. 187–88.

- ↑ Gary Dickson, "Crusade of 1309", in Alan V. Murray (ed.), The Crusades: An Encyclopedia, 4 vols. (ABC-CLIO, 2017), vol. 1, pp. 311–13

- ↑ Norman Housley, "Pope Clement V and the Crusades of 1309–10," Journal of Medieval History 8 (1982): 29–42.

- ↑ Gábor Bradács, "Crusade of the Poor (1309)", in Jeffrey M. Shaw and Timothy J. Demy (eds.), War and Religion: An Encyclopedia of Faith and Conflict, 3 vols. (ABC-CLIO, 2017), vol. 1, pp. 211–12.

- ↑ Christopher Tyerman, "England and the Crusades, 1095–1588" (University of Chicago Press, 1988), p. 172]

- ↑ Christopher Tyerman , England and the Crusades, 1095–1588 (University of Chicago Press, 1988), p. 172

- ↑ Sylvia Schein, Fideles Crucis: The Papacy, the West, and the Recovery of the Holy Land, 1274–1314 (Clarendon, 1991), p. 234.

- ↑ Anthony Luttrell, "The Hospitallers at Rhodes, 1306–1421", em inglês, acesso em 27/07/2021.

- ↑ Barbara Tuchman. A Distant Mirror. Alfred A. Knopf, Nova Iorque, 1978, p41f.

- ↑ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Crusade of the Pastoureaux". Enciclopédia Católica. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ↑ PASTOUREAUX, em francês, acesso em 28/07/2021.

- ↑ Chroniques, em francês, acesso em 28/07/2021.